The Art Of Writing A Good Introductory CTF Challenge

Making challenges for beginners is a lot, lot tougher than making challenges for seasoned CTF players. The yoke of sparking fresh interest in cybersecurity always feels heavy on my shoulders, and there’s just so much to consider. Every time I try, there’s always something new I know I could improve on.

This post is a reflection on my personal refinement of the process, and my definition of a good introductory CTF challenge. It’ll be framed by the challenges I’ve made in the past, my interactions with people attempting them, as well as my own journey as a beginner many years ago. Let’s start in 2023.

2023 - Cyberthon

This was a CTF held for Junior College students in Singapore. CSIT, one of the organisers, kindly offered some of us working with them at the time the opportunity to write challenges for the competition.

On JC students

It was exciting, going from a participant many years ago to a challenge author. However, unlike the earlier CTF I wrote for, TISC 2023, this CTF was the gateway into cybersecurity for many students. The weight of this responsibility ate at me incessantly.

I know that some JC students are very skilled. These aren’t the people I’m writing for. This post, and all challenges contained within, are written with the beginner in mind. Cyberthon is organised for getting more JC students into cybersecurity for publicity and recruitment. This is different from regular CTFs, where the goal is to inflict as much pain as possible over the weekend.

The data science category

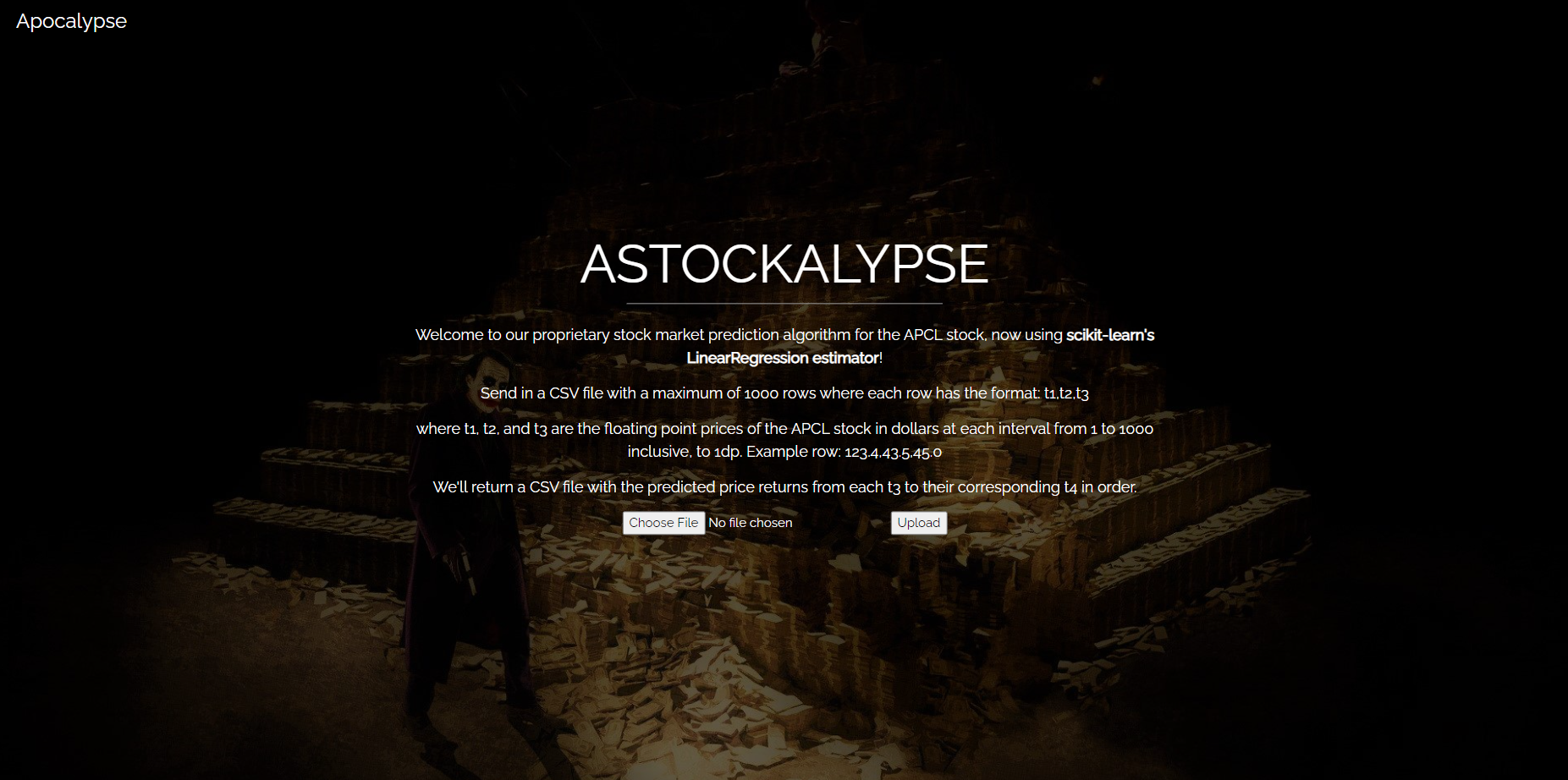

I was tasked with writing a challenge for the data science category.

I didn’t have a lot of challenge creation/teaching experience back then, so most of my decisions were shaped by my experience as a participant in 2020/2021. As a participant, I remembered thinking that the kaggle-style challenges weren’t extremely relevant to cybersecurity, so I ignored them. I wanted to break free from the model training convention and do something a bit different. Adversarial ML seemed the most relevant to cybersecurity, so I based the challenge around model stealing.

This was something I think I did well in. AI attacks have been getting more and more prevalent recently, and a bunch of AI CTFs have been popping up over the past few years, with the sole focus of exploiting deployed ML models. It was a realistic attack, put forth in a simple and understandable way to participants. If participants are able to contextualise the attack to the products they use/design, they’re more likely to be sold by the importance of security.

Why Cyberthon wasn’t effective for me

In JC, I was into robotics and general software development. Cyberthon failed to get me interested in cybersecurity. I wanted to think about why, and how I could tailor my challenge to students like me.

I remember being very frustrated and giving up often during Cyberthon, regrettably so. It was not a pleasant experience for me, and at the time, I chalked it up to cybersecurity having a high barrier of entry. When I was creating my challenge, I wanted it to be simple and straightforward to lower that barrier and give newer teams the satisfaction of a solve. I achieved my goal somewhat; over 40 teams solved my challenge. But were they satisfied?

It’s hard to say. Coming up with the solution was really easy, even for new teams. Knowledge of python and scikit-learn was all you needed, and examples of the latter were everywhere on the internet. I thought the solution was clever enough to satisfy the students, but after talking with many students, I realised that most of them craved a bit more of a challenge. It made sense: satisfaction comes from learning, and the best learning is often done through struggle. It seems that I’ve underestimated my demographic.

2024 - Cyberthon

The next year, I was given the opportunity to author a challenge for the web category. This time, I was armed with the experience of the year before, and was ready to write an effective introductory challenge. At least that was what I had in mind.

My challenge ended up being TOO difficult…

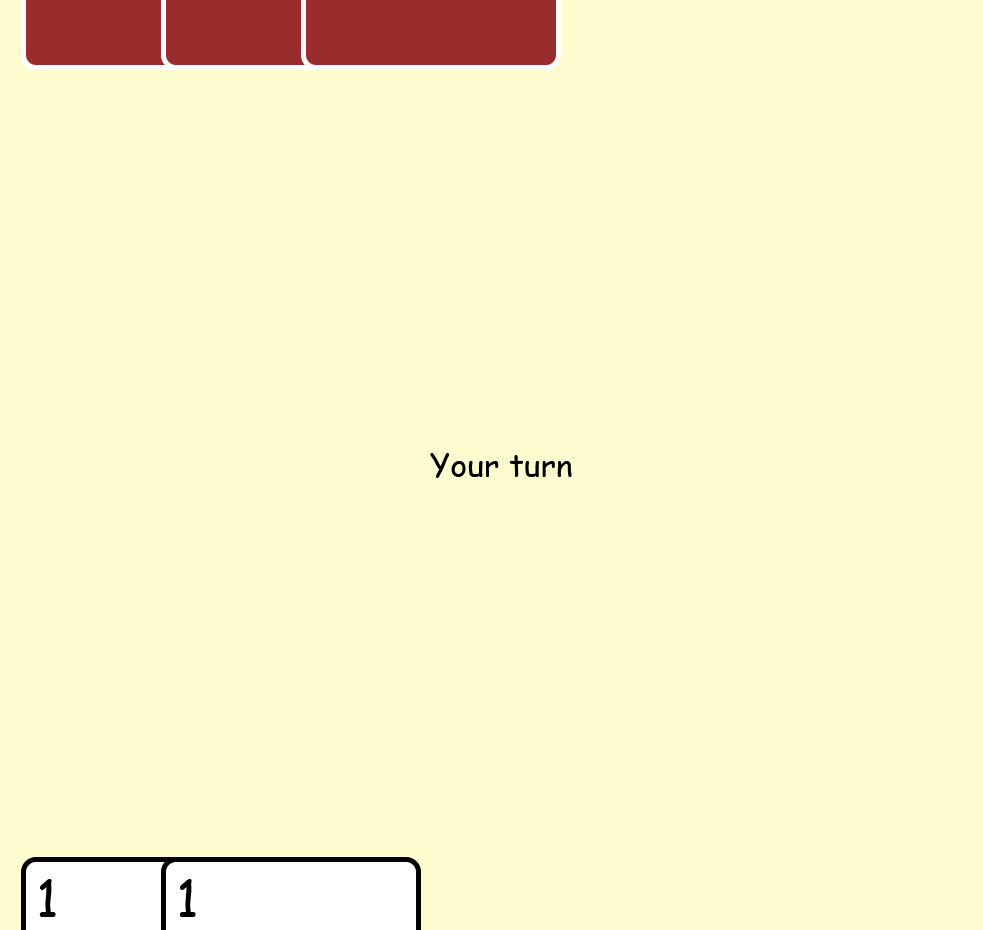

I wanted to give students a real challenge this time, to enhance the learning experience. I cranked the difficulty up a notch or three, and based it on a unique and cool vulnerability: HTTP request smuggling. I even used it in an interesting and realistic way: to interfere with your opponent’s moves in an online card game. What could go wrong?

Only one person solved my challenge. I’m pretty sure they were the only person who attempted the challenge within a reasonable capacity as well. God, balancing is tough.

I had even suspected that the challenge was too difficult before the competition. It was hard to gauge the level of difficultly I should’ve gone for, especially since I only had a lower bound. The deployed challenge even included a bunch of free hints just to put a bandaid on the gaping wound.

The folly of indulgence

Looking back, it was also partly my own hubris that led to this. In my excitement, I failed to consider the student perspective with as much nuance as I should have. When writing introductory challenges, the student experience always comes first. My urge to share cool things I’ve learnt, my portfolio, all that comes secondary to the target audience. Having the ability to teach and guide a new generation of people interested in cybersecurity is a hefty onus. It has been tough to keep this in my mind always. Often, I find myself straying from this and going on long rambles. I try to remind myself, but do stop me if it slips and I go too far.

2025 - Greyhats Welcome CTF

This time, I had a better idea of the difficulty I was going for. Not too trivial, such that solving the challenge didn’t require much pondering, but not difficult. When writing the challenge, I constantly make an effort to think from a complete beginner’s perspective; my idea of not difficult is very much not universal. My idea was to come up with a challenge that seemed, to me, right on the verge of becoming trivial. Hopefully I’d hit just the right spot.

The drafting plan

When designing the challenge, my strategy was to start with a trivial vulnerability in a common language as a base. This could be SSTI, XSS, etc. I’d then add only one trivial obstacle. It could be a really simple WAF, or a hidden form field, but that’s all I could add. I ended up deciding on an SQLi, but the app overwrites the injectable variable with another value before the query, requiring participants to perform a simple bypass.

This method worked surprisingly well. Over 70 teams managed to solve the challenge, and I got some nice comments about the learning experience it provided. Many teams struggled for quite a while on it, but most of them were able to get the flag before the CTF ended. That’s satisfaction.

Okay, enough praise

The challenge didn’t come without its flaws. In hindsight, the challenge was too unfocused, and led many solvers down many different rabbit holes. I’d argue that rabbit holes are fun for regular CTF challenges, but we’re prioritising the main learning objective here, so

- I shouldn’t have included the Docker setup scripts in the dist. These are useful and important for other CTFs, but only serve to confuse beginners. They wouldn’t be spawning local instances anyway.

- The scripts are too long, and contain useless information “for the plot”. The website needs to be barren, to focus the student’s attention on the actual vulnerability.

- PHP is not a very readable language for beginners. I am not sure why I even used PHP in the first place. In hindsight, having readable, simple to follow code is very important, and a language like python would fit the bill a lot better.

What about the grander scheme of things?

CTFs don’t just have one challenge per category. So what now? Just make everything a good introductory challenge?

Well no. Not only do you need to cater challenges for teams that are slightly more skilled, you also need to give teams room to grow after completing an introductory challenge. In my opinion, having a linear, unconfused path to follow is best, especially in something as hard to find your footing in as cybersecurity, so a harder challenge needs to build on an introductory challenge in a meaningful way.

This could be something like having the same base vulnerability but with a taller obstacle (a more robust WAF), or chaining something simple on top of the base.

In a category with 5 challenges, I’d like 2 introductory challenges, 2 challenges that build on each one, and a final hard challenge. It’s more à la workshop/training platform than actual CTF, but for something specifically meant for people just starting out, I think thats fine.

What about people smurfing? YOU NEED SMURFCATCHER CHALLENGES TO KEEP THEM AT BAY!!!!

For CTFs like Cyberthon with a wide range of skill levels, sure. Maybe put one or two in each category. For completely introductory CTFs? Not necessary.

2026 - ?

I’ll be making challenges for Welcome CTF again, probably. Maybe for other introductory CTFs too. I’ll update this post with any further insights I get. Thanks for reading this far. I hope you learnt something from my blundering around.